Those who have followed the political scene in Turkey over the past few weeks have watched the unfolding of a number of overlapping major events. Among the breaking stories are those related to the corruption crisis, which has resulted in a significant challenge to the power of the AKP government; the open conflict between Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his important former ally Fethullah Gülen; rising interest rates, which have drawn international attention; the state of relations with the EU (particularly in the wake of Erdoğan’s recent trip to Brussels); the Turkish state’s role in Syria, especially in light of the Geneva II conference; and the imminent arrival of the one hundredth anniversary of the Armenian Genocide in 2015, especially given the recent anniversary of the assassination of Hrant Dink. All this is in addition to the ongoing question of the “peace process” and the Kurdish question more generally, as well as the myriad political issues brought to the forefront by the Gezi Resistance last summer. And all this arises in the wake of local elections to be held at the end of March (the Al Jazeera Turk website has posted a resourceful interactive map of local elections)—and, beyond that, the presidential election in August, in which Erdoğan will surely compete and which will be seen as a test of the AKP’s continuing hegemony.

In light of these ongoing developments, which have resulted in a political situation that appears to be changing by the minute, even the most seasoned analysts (or at least those not satisfied with falling back on familiar platitudes) are having trouble articulating a response. So I asked several members of the Turkey Page Editorial Team to help Jadaliyya readers begin to formulate an understanding of some of the evolving issues of this political moment. To follow these events on a more regular basis, see the many resources collected in our weekly Turkey Media Roundup.

The deportation of Mahir Zeynalov, an Azeri journalist on staff at Today`s Zaman, reflects both the fragility of the free press in Turkey and the further schism between Fethullah Gülen and Erdoğan. Today`s Zaman, as the English-language affiliate of the Zaman daily, is aligned with the Gülen movement. Because of its right-wing and neoliberal affiliation with Gülen, the paper is generally considered a pro-government mouthpiece. The paper`s editorial line normally only parts with the government`s view when Gülen and the government do not agree.

For context, one notable previous example of such a difference of opinion was the Mavi Marmara incident. While Erdoğan seized the opportunity to shore up his profile in the Middle East as a crusader for Palestinian rights, Gülen decried the Mavi Marmara as being provocative and claimed that those on board should have sought permission from Israel to reach Gaza (apparently missing the point behind the idea of nonviolent civil disobedience.) Today`s Zaman initially published only outrage, but later softened its stance once Gülen`s pronouncement came out.

Zeynalov`s career in some ways mirrors this tension within Today`s Zaman; he often represented the government`s view, but has lately been a combatant in the war of ideas of Gülen versus Erdoğan. During the Gezi Resistance, for example, Zeynalov consistently downplayed the significance of the protests and at times defended Erdoğan`s handling of the police repression.

However, during the Gülen-Erdoğan rift of late, he has come down firmly on the side of Gülen and has paid the price for doing so. After being sued by Erdoğan for critical comments he made on Twitter in December, he was deported in early February. Since his deportation, his latest column at Today`s Zaman has harshly criticized Erdoğan and says that the Gülen movement “cannot lose the battle.”

The lesson from Zeynalov`s deportation is this: No one is safe. Not even journalists who have been fiercely loyal to Erdoğan will be excused for siding with Gülen.

Zeynalov was an easy target because he is Azeri and was attached to a Turkish publication. Were he writing for a European or American outlet, it would not be as safe a decision to get rid of him. That said, other journalists have been deported before: for example, in 2010, Inter Press Service`s Jake Hess. But Hess was resolutely critical of the government and reported on the Kurdish issue from the southeast. Zeynalov was a loyalist with conflicting allegiances in a power struggle. If even he can be deported, then the state of the free press in Turkey is clearly in jeopardy.

The debates on local elections are a constant part of the rapidly-changing political landscape in Turkey. One very important position is that of the mayor of Istanbul. The metropolitan municipality seat is currently held by the AKP`s Kadir Topbaş; this is also the position from which Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan made his leap towards Ankara. Officially home to fourteen million people, but often estimated to be around twenty million, Istanbul`s metropolitan municipality is an important stronghold and a strategic spot for political maneuvering for any party or politician that controls it. That is why the fast-approaching local elections of 30 March have become a hot topic for many, as urban politics also gained in importance after the Gezi uprising of the summer, and, more recently, as the links of the corruption probe to the construction industry became evident.

Meanwhile, urgent debates have ensued between the constituents of Gezi about who the right candidate should be to break the AKP`s hold on the municipality. The founding Republican People`s Party (CHP) chose Mustafa Sarıgül as its candidate, while the newly founded Democratic People`s Party (HDP) chose former Peace and Democracy Party (BDP) and current HDP parliamentarian Sırrı Süreyya Önder for the mayoral race. Upon the announcement of the candidates, the opposition was quickly polarized between those who strongly advocated that Sarıgül is the opposition`s only chance at challenging the AKP for Istanbul’s mayorship, and those who advocated Önder as the most natural candidate for the seat due to his prominent role in the Gezi Uprising. Long-standing disagreements over whether the CHP qualifies as a party of the left resurfaced, fueled by the CHP`s open gestures towards the right in its local election campaigns. One of the most interesting pieces I have read so far was a profile of Sarıgül on Reuben Silverman`s blog. The piece is a comprehensive account of Sarıgül`s history as a politician, and through tracing his fascinating career, Silverman also gives an idea of recent Turkish political history and the CHP`s place in it. In my mind, pieces such as this one are rare but extremely necessary, as they clarify current political positions by placing them in historical context.

Meanwhile, independent news network Bianet recently published an interview with the CHP and HDP candidates for Beyoğlu municipality, where Taksim Square and Gezi Park (among other sites of concern for Istanbul`s urban politics) are located. The CHP nominated Aylin Kotil, an economist who is also married to Sarıgül, for this seat (see Silverman’s article on Sarıgül for the full connection and history). The HDP candidates are architect Korhan Gümüş, who was active during the Gezi Uprising and is one of the founders of Taksim Platform, a key part of Taksim Solidarity, and twenty-six-year-old Seyhan Alma Ürek, an activist in the Kurdish women`s movement from Roboski/Uludere. The interview includes questions to the candidates about Gezi Park, the current state of Taksim Square after the partial implementation of the Taksim Square Project, the ongoing hardships of exercising the right to assembly in the Taksim area, the role of women in local politics, and ongoing urban transformation/gentrification projects in the Beyoğlu district.

Another important contribution to the analysis of local elections is the recent research done by a team of anthropologists and sociologists in Turkish universities, including our Jadaliyya Turkey Page Co-Editor Nazan Üstündağ. Her three-part analysis of the research findings (Part One, Part Two, Part Three) provide a general picture of the elections from the perspective of the voters in Turkey. We also continue to cover the local elections in our weekly Turkey Media Roundup; an archive of pieces from the last few months can be browsed here.

The Gezi Uprising and graft probe showed that urban politics is an increasingly important aspect of social and political life in Turkey. The Networks of Dispossession, a collaborative project conceived during Gezi, shows the closeness of the ties between capital, political power, and urban infrastructure projects. In this vein, I have been following the rising Kuzey Ormanları Savunması (Northern Forests Defense) in Istanbul, a movement that has been emerging in the villages of northern Istanbul against the usurpation of land and natural resources for the third bridge and third airport projects that are underway.

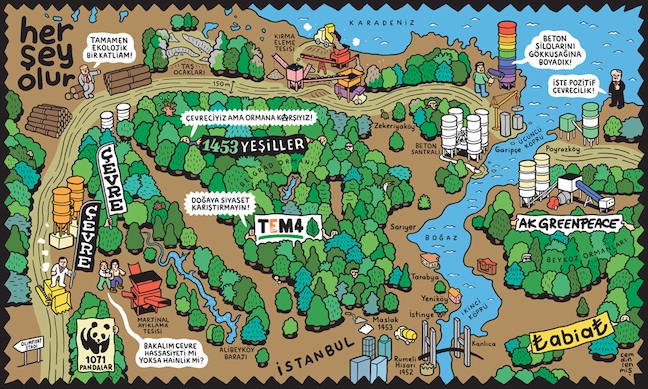

Here is a political satire map of the Northern Forests Defense by caricaturist Cem Dinlenmiş, poking fun at the AKP`s dubious claims of environmentalism while the resistance against the government`s construction projects in the area continues.

[Cem Dinlenmiş, "İstanbul’un kuzey ormanları" ("The Forests of Istanbul"). Image via Tumblr.]

During these last two months I have been following several issues that I think have been overshadowed by current events (specifically, the notorious fight between the Erdoğan government and the Gülen Movement). I will comment here on one of these: namely, the conflict between the Kurdish Freedom Movement and the Armenian community in Turkey.

When Bese Hozat, the co-spokesperson of KCK, declared recently that the Armenian and Greek lobbies play a role in preventing peace and the solution of the Kurdish issue, her words rightfully disappointed Armenians, as well as the democratic public at large. Several Armenian journalists have associated Hozat`s words with the official discourse of the Turkish state and expressed resentment, calling on Hozat to either provide evidence for her statement, or else to issue an apology or at least a correction. More hostile writers (mostly non-Armenians) have argued that Hozat’s statement revealed the subconscious of the Kurdish Movement, which has not faced up to the Armenian Genocide and the role Kurds played in it (see, for example, the commentary by Ahmet İnsel, who is one of the more sophisticated liberal intellectuals in Turkey).

Still others have claimed that the praxis of the Kurdish Movement is a testimony to their genuine willingness to come to terms with the past and to create a future where not only the rights of Kurds, but the rights of all who have been wronged by the Turkish state, will be granted. Among these, Ayşe Günaysu’s article in Özgür Gündem stood out. Günaysu paraphrased the writings of a member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Taşnaktsutyun) in Armenian Weekly who praised the hospitality he encountered when he attended a meeting organized by the Peace and Democracy Party’s Youth Organization. Günaysu invited both the KCK and those who criticize them to pay more attention to what’s happening on the ground: specifically, the genuine attempts of Kurdish municipalities to invite Armenians to their land and to remake Kurdistan as a place of plural cultures. Others have pointed to the newly-published Rojava Constitution, where sovereignty is multiculturally defined.

Meanwhile, Hozat has further explained herself in an attempt at clarification, arguing that her words never targeted the Armenian people, but only nationalist lobbies, and that she is as critical of them as she is of Jewish, Turkish, and Kurdish nationalists. Meanwhile, Hrant Dink`s funeral was attended by thousands, many of them Kurds. Finally, the Armenian-Turkish newsweekly Agos published a letter sent by Abdullah Öcalan, declaring his support for and admiration of the Armenian people, and their capacity to survive, struggle, and witness what befell them. He stated that what happened in 1915 was indeed a genocide. Several contributors to Agos stated that they appreciated the letter and were satisfied with the fact that Öcalan defined the events of 1915 as genocide, when until now no Turkish authority has ever done so. However, they also noted that the letter still made reference to “lobbies,” a term borrowed from the official language of the state that has hurtful connotations to Armenians and works to de-legitimize their political activity.

I find these events to be extremely important for the political and social landscape in Turkey. I have already written about these a bit, so let me paraphrase what I think. The events reminded me of Rene Girard`s take on violence. He writes that when institutions cannot function and when people and values become indiscriminate, when there are no institutions to maintain hierarchies, people look for a sacrifice—a sacrifice that will give them pause, calm them down, and cause them to reflect and to build hierarchies between what is important and what is not, what is hurtful and what can be allowed to slide. It must be a sacrifice close enough to them so they can relate to it, but distant enough so that they can eventually forget it. Non-Muslims in Turkey have always been the first to be sacrificed in such circumstances. So it seemed to be nothing new when suddenly the whole conflict in Turkey, specifically the obstacles to peace, were explained away by putting the blame on the Armenian lobbies. And when in return Hozat and the KCK were accused of having revealed their unconscious, which is still "uncivilized," according to some Turkish liberals, this also seemed to follow the pattern.

But after all, that is not how things ended. Kurds, Armenians, and others who identify themselves with the oppressed in Turkey refused to let it go, and instead entered into a very productive (and still unresolved) dialogue. The important thing, which can give us hope, was that the dialogue happened between those on the margins—between Öcalan and KCK, on the one hand, and Armenians, specifically those who gathered around Agos and Nor Zartong—all of whom have suffered immensely as scapegoats in Turkey.

The debate itself has instated Armenians and Kurds as major players in Turkey, more open to dialogue, peace, solutions, and acceptance, despite their differences, than any Turkish political public actors we have seen. And all this was happening while two Muslim-right-identified political bodies were fighting a fierce battle with tapes, scandals, curses, and censorship.

On 18 July 2013, at a moment when discussions about the grievances of Alevi citizens in the face of a Sunni-Hanafi dominated state abound in Turkey, Prime Minister Erdoğan made public another one of his all-knowing statements:

“They are trying to divide us as Alevi and Sunni. What is behind this discrimination? If Alevism is loving Hz. Ali, I am a perfect Alevi. [Hz. Ali] was our Prophet’s groom, and a warrior. We will not be fooled by their provocations, incitements, and games. We will instead share with them our love for Turkey and our love for our nation."

In his uncompromising and aggressive reaction to the social scientists he met with to discuss the Gezi Protests in the midst of the crisis on 13 June, Erdoğan had also declared defiantly that he knew psychology and sociology well, and didn’t need to learn from the social scientists present to understand the societal dynamics behind the protests. Alevis’ systematic dispossession by the state—through the denial of state funding to Alevi institutions of religious practice, not recognizing Alevism in religious texts taught in state schools, and reducing Alevism to a “folkloric” and “cultural” color within Turkey’s diversity—are only part of the story here, and Erdoğan apparently knows them all too well too.

Well, was there anything in Turkey, or in the world for that matter, that Erdoğan did not already know, and hence needed to learn? When Levent Pişkin, an LGBTI and queer activist and the HDP Beyoğlu district Co-President, heard Erdogan’s all-knowing statement about Alevis of Turkey, he certainly thought so. In response, Pişkin tweeted in Turkish: “I wait for the day Erdoğan declares ‘I am a perfect ibne (faggot), and we don’t need to learn about being a faggot from you.’ Kisses.” He ended his tweet with the hash tag #AnayasadaLGBT, referring to an ongoing campaign initiated well before the Gezi Protests about LGBTI and queer rights in Turkey’s new constitution, which itself remains stalled in its drafting phase.

Erdoğan filed a lawsuit for slander propagated via media against Levent Pişkin for the use of the word ibne. In an op-ed piece penned for BiaNet, Pişkin, a lawyer by trade, wrote that far from being a discriminatory word, ibne was an identitarian term claimed by many members of the LGBTI and queer communities in Turkey, as evidenced by the thousands of banners carried during the Pride March with the slogan Velev ki Ibneyiz: “And yet we are fags.” Tracing the historical roots of the term ibne back into Ottoman lexicon, Pişkin further claimed that the term refers “not to a slander attempt, or a behavior, but rather to social existence.” Going back to the Turkish Language Institute’s dictionary that defines ibne as “a passive homosexual man,” Pişkin asked: “Where and when does the use of a term that refers to sexual orientation constitute a personal slander?” Pişkin also filed for an investigation of Erdoğan`s lawsuit, maintaining that not his own use of the term ibne, but rather Erdoğan’s taking it as a slander, itself constitutes a personal slander against Pişkin (who identifies as ibne) and the larger LGBTI and queer communities in Turkey.

Some have argued that the LGBT Block’s presence in the Gezi Protests now remains a distant memory of an extraordinary alignment, with no tangible achievements gained since the "once-promising gay revolution." I beg to differ. First, I want to suggest that such a conclusion obscures, rather than reveals, the history of the LGBTI and queer communities’ political struggles in Turkey that extends well beyond their presence in the Gezi Protests. Second, it ignores the ways in which LGBTI and queer politics have transformed and reorganized themselves after Gezi and moved beyond a strictly identitarian politics that only vocalizes the grievances of “sexual minorities.” As the ongoing ibne court case exemplifies, the LGBTI and queer activists’ intervention in an allegedly “separate” debate about state-sponsored religious sectarianism and systematic dispossession of Alevis charts out a different mode of conducting queer politics in Turkey and remaining in solidarity with other communities in doing so. And for those readers who are fans of “hard” political gains, it might be important to note that in Istanbul alone, the upcoming municipal election lists now feature six LGBTI and queer candidates from the CHP (The People’s Republican Party) and HDP (The Peoples’ Democratic Party). The ibne court case, as well as the case for queer politics in Turkey, in brief, remains open and contested, with Erdoğan seemingly well situated to learn a new thing or two.

![[People gathered in front of a hospital in Istanbul on 5 January to celebrate the fifteenth birthday of Berkin Elvan, who has been in a coma since 15 June, when he was shot in his head with a teargas capsule while walking to buy bread. Photo by Adnan Onur Acar/Nar Photos.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/roundtable_photo.jpg)